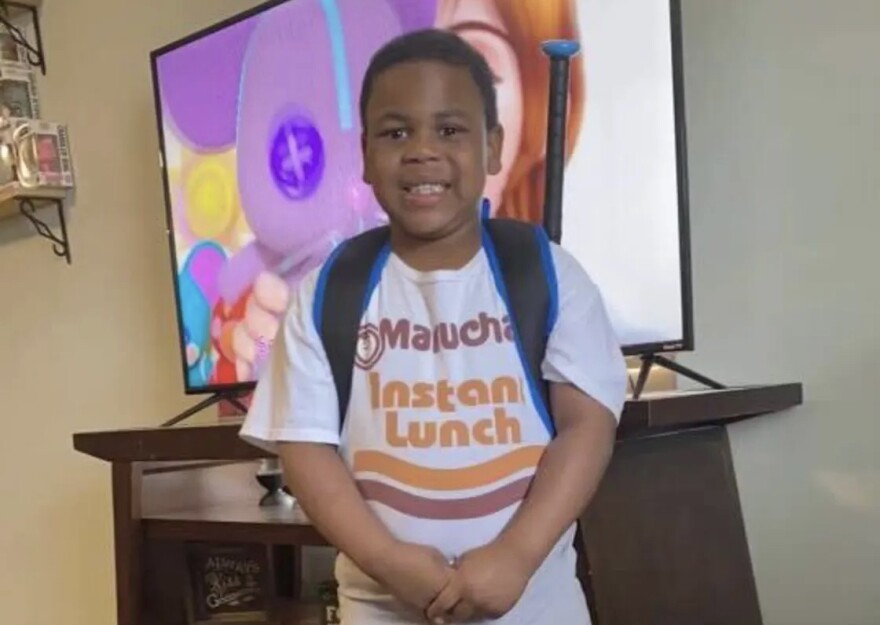

On July 17, 2022, a pair of staffers at Louisville’s Brooklawn foster care facility put a then 7-year-old boy named Ja’Ceon Terry in a physical restraint, with one holding his legs out straight and another pushing against his back until his nose almost touched the floor. They held Ja’Ceon until he vomited, lost consciousness and died.

The Jefferson County coroner ruled the death a homicide.

Three years later, the Jefferson Commonwealth’s Attorney is still reviewing the case, according to Erran Huber, a spokesperson for the prosecutor’s office. Huber did not respond to multiple requests for additional details about the scope of the review, the status of any ongoing investigation and the reasoning behind the three-year delay in deciding if criminal charges are warranted.

The lack of movement in the case frustrates current and former lawmakers who want someone held accountable for Ja’Ceon’s death.

“From what I know, there was some type of misconduct that occurred,” said Kentucky state Sen. Keturah Herron, a District 35 Democrat. “There has to be some type of accountability.”

The Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting in 2023 obtained records that detailed the tragic final hours of Ja’Ceon’s life. The records, compiled by investigators with the state’s Cabinet for Health and Family Services, describe the verbal abuse, public shaming and neglect Ja’Ceon endured before the two staffers, Deborah Francis and Jillian Parks, entered his room and held him down until he went limp.

The records also highlight a series of systemic failures that contributed to Ja’Ceon’s death — the staffers failed to avoid triggers known to provoke Ja’Ceon, they violated policy by placing him in a physical restraint outside the view of cameras and they mischaracterized the events to state investigators.

Attica Scott, a former Louisville Metro Council member and Kentucky state representative, said the prosecutor’s delay makes her think “there’s something that needs to be hidden, or he’s just not a priority.”

“Justice shouldn’t take this long for Ja’Ceon,” she said.

In January 2023, Scott penned an essay on Medium calling on Mayor Craig Greenberg to direct the Louisville Metro Police Department to arrest the two women who held Ja’Ceon down. She pointed out his campaign slogan of moving Louisville in “new direction” and said “a new direction would be to hold public employees accountable when they kill children.”

“I have seen time and time again how our governmental entities don't prioritize Black lives,” Scott told KyCIR.

Asked if Greenberg ever directed LMPD to arrest the two staffers, his spokesperson, Kevin Trager, told a reporter to contact the Commonwealth’s Attorney for questions about the case.

“Ja’Ceon’s death was a tragedy and our thoughts continue to be with his loved ones,” Trager said.

The two staffers who restrained Ja’Ceon were fired weeks after his death and state officials revoked Brooklawn’s license to operate psychiatric treatment facilities, the unit where Ja’Ceon lived. His foster parents reached a private settlement in May 2023 with the company that operated the facility.

But for Scott, this is not accountability.

“We need more from the Commonwealth’s Attorney and we need it now,” she said. “We needed it last year. We needed it the year before, but we absolutely need it now.”

Criminal prosecutions in cases like Ja’Ceon’s are rare, said John Myers, a professor at University of California Law San Francisco and leading child abuse expert.

“This is not an easy case,” he said. “If I was a prosecutor, I’d be pulling my hair out.”

Myers said he worked in a psychiatric unit when he was younger and has an idea of the complex and challenging situations staffers encounter. He said they’re “caught in the middle of an impossible situation” because kids, at times, can turn violent and force is necessary.

Mistakes happen, he said. And in a case like Ja’Ceon’s, prosecutors must consider if a staffer is negligent or if they intended to harm a child, Myers said.

“I think lots of people in the public would say, ‘this is easy, this little kid was killed and somebody needs to pay.’ I think that's naive and doesn't actually have an understanding of the complexity of taking care of these children,” he said.

After Ja’Ceon died, former KyCIR reporter Jasmine Demers examined other cases of physical, emotional and sexual abuse at state-licensed residential foster care facilities. She found a system marred by investigative gaps, in which kids were rarely believed — if they were interviewed, at all.

She highlighted data from the nonprofit Kentucky Youth Advocates that show how state officials depend on residential care facilities as the number of willing foster families drops. The group also chronicled the troubling experiences of the kids that live in these types of facilities.

Terry Brooks, the executive director of Kentucky Youth Advocates, said Ja’Ceon’s death is a reminder that kids need a system of rigorous and responsive accountability.

Brooks hopes Ja’Ceon’s death sparks a change.

“This young man's tragic death should be the canary in the coal mine calling for a fundamental - and not an incremental - revolution in how we care for kids in the child welfare system after removal,” he said. “As a state we are failing kinship and foster kids in ways large and small.”