This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of the death of a child.

Two nurses, a chaplain and a Louisville police detective were at the 7-year-old boy’s bedside when his time of death was called — 4:48 p.m. on July 17, 2022. His emergency room chart noted that he was a foster child with no parents.

Ja’Ceon Terry was already unresponsive when first responders arrived at Brooklawn, a residential care center for foster children in Louisville, and began chest compressions. A staffer told an EMT that they’d had the boy in a “bear hug” due to an “outburst,” and suddenly felt him stop resisting.

There was vomit everywhere, first responders said. It was in Ja’Ceon’s mouth and throat, running down his cheeks and on the floor. The EMTs had to suction it out before they could intubate him, to try to save his life.

The first responders and hospital staff performed CPR for more than two hours, but Ja’Ceon’s heart never restarted.

A report obtained by the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting from the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services offers new details into what happened on that day a year ago. The state’s investigation found that in his final hours of life at Brooklawn, Ja’Ceon was publicly shamed, verbally abused, left in his room alone for nearly six hours and held down by two staff members until he lost consciousness.

Records in the case underscore a number of systemic failures that contributed to the death of a child who had experienced trauma after trauma in his short life. Staff ignored a therapist’s advice to help him avoid triggers that set him off. In violation of numerous state and facility policies, he was placed in the hold that led to his death outside the view of cameras — for no more than saying he’d throw a plastic water bottle at someone and using a swear word. And when the time came to document the hold, state investigators found that the staff members mischaracterized what happened.

State officials have since revoked Brooklawn’s license to operate its psychiatric treatment facilities, the unit where Ja’Ceon died. But they resumed foster placements at Brooklawn’s other programs in May.

The two staff members who put Ja’Ceon in a hold — Deborah Francis and Jillian Parks — were fired from the facility in September. Neither could be reached for comment.

The Louisville Metro Police Department said the criminal investigation is still ongoing, but that no charges have been filed a year after his death. The Commonwealth Attorney’s office told KyCIR that the case is currently being reviewed by a prosecutor. Brooklawn officials did not respond to requests for comment.

This story draws from court records and the investigative report from the Office of the Inspector General, released to KyCIR in response to a public records request. The report outlines information gathered from video evidence at the facility as well as interviews of 25 staff members, five residents, three first responders and three state social workers.

Ja’Ceon’s life

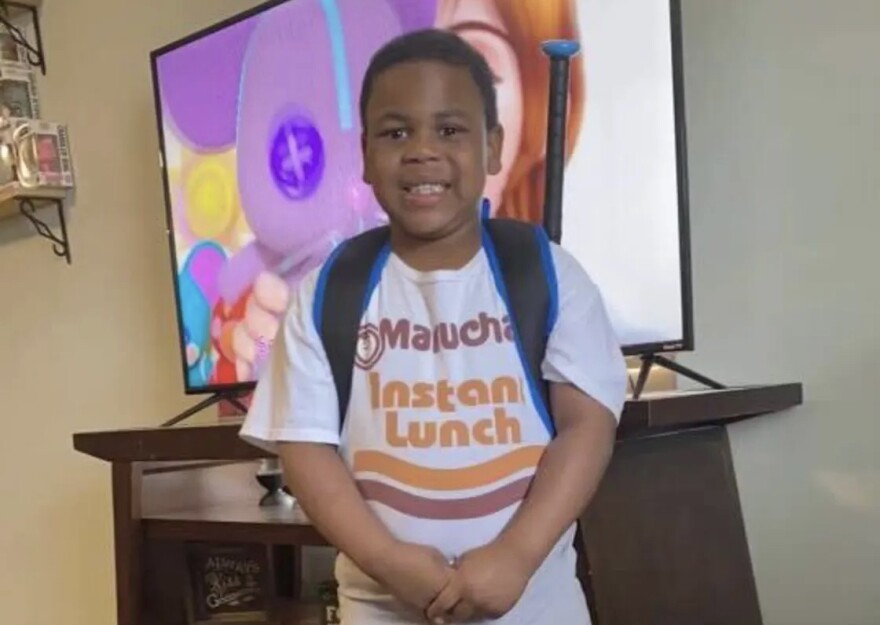

Ja’Ceon was born on August 10, 2014. By the time he entered state care four years later, the report shows Ja’Ceon had already witnessed drug use, violence and prostitution in his home. He was often neglected and left alone, and it was suspected that he was sexually abused.

When he was 4 years old, Ja’Ceon reportedly lived in a homeless shelter with his mom and two brothers. His family wasn’t allowed to stay at the shelter during the day, so they often went to the mall. On a day like this, the state report said, Ja’Ceon was wandering around the mall unsupervised and found an ATV. He drove it around the mall, crashed into a glass window and hit a pedestrian. Ja’Ceon and his brothers were placed in state custody that same day, the report said. His mom and dad’s parental rights were terminated on August 10, 2021, his 7th birthday.

From then on, Ja’Ceon bounced from foster homes to psychiatric hospitals and residential care facilities. In June 2022, he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for what was described as “aggressive and sexually acting out behaviors'' while in a foster home. His foster parents said he was “destructive, disruptive and aggressive with adults and peers,” according to the state report, and that they couldn’t care for him anymore. The state admitted him that same month to Brooklawn.

The facility, in Louisville’s Bashford Manor neighborhood, is owned by Uspiritus and partners with the state to provide long-term and therapeutic care for Kentucky’s most vulnerable children. These types of facilities are meant to be a safe haven for children with intense histories of trauma. Ja’Ceon was admitted to Brooklawn’s psychiatric care unit, which provides care for children with severe mental illness.

Though he was big for his age at 4 foot 4 and 114 pounds, a staff member at Brooklawn described Ja’Ceon as more like a 2-year-old than a 7-year-old, the investigation said. He was diagnosed with mild intellectual disabilities, ADHD, disruptive mood disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. He was often defiant and had negative reactions to direction from staff, like cursing and throwing things.

While he struggled to adjust to routines at Brooklawn, one staff member in the report said she thought he was making improvements day by day. She said Ja’Ceon seemed to crave nurturing and longed for touch and one-on-one attention. The night before he died, he woke up at 3 a.m. and asked her to cover him with a blanket.

Ja’Ceon’s final hours

Shift Supervisor Deborah Francis, referred to in the state's report at Shift Supervisor #1, reported to work at Pilots Cottage on Brooklawn’s campus at 8 a.m. on Sunday, July 17, 2022. She and a new employee, Amanda Whitlow, referred to as YCW #1, would be responsible for the care of nine residents until 2 p.m. that afternoon. The investigation revealed that there should have been three people working that morning to meet the required staffing ratio of three residents to every one staff member.

Francis told investigators she heard Ja’Ceon had been misbehaving the night before and decided to keep him in his room all day — a decision that wasn’t approved by clinicians or management and went against the facility’s seclusion policy.

Seclusion should only be used when other interventions have not worked and there is a risk of imminent harm, according to the policy. Even then, the maximum duration of seclusion allowed for a child Ja’Ceon’s age is one hour, with check-ins every 15 minutes. And someone should be sitting outside of the seclusion area the entire time.

Camera footage showed that Ja’Ceon was alone in his room for six hours that day. His psychiatrist told investigators that type of treatment would likely trigger memories of a previous experience that involved him being locked in a room.

A staffer brought breakfast to Ja’Ceon’s room, a half hour later than everyone else, at 10:41 a.m. Interviews and video footage show that five minutes later, Ja'Ceon stuck his hand outside his door, which is what children at Brooklawn were told to do when they needed to get staff’s attention. No one was sitting outside his door, and no one responded.

He signaled again at 10:59 a.m.

Again nearly an hour later, at 11:56.

When he signaled once more at 12:15 p.m., video footage showed parts of his yellow shirt and shorts seemed darker than the rest, like they were wet. He had an accident.

Francis walked over to Ja’Ceon’s doorway with dry clothes and a towel and waved him out of his room. Whitlow, who was supervising the other residents in the common area, said Ja’Ceon was trying to hide the front part of his body. According to Whitlow and other residents, Francis walked with Ja’Ceon past the common area and said to them, “This is what big boys/girls do. They piss on themselves. And you really pissed on yourself.”

Some of the residents laughed at him, Whitlow said. In the video, Ja’Ceon is covering his face with a towel. After showering, the 7-year-old was sent back into his bedroom with a mop.

When investigators asked her about the incident, Francis denied that she spoke to Ja'Ceon in the way the others described.

But Whitlow claimed Francis made other comments that concerned her that day: When they started their shift, Francis told Whitlow that she was upset with Ja’Ceon because “he ruined her church day” and that “she was going to hold him and make him throw up.”

Hours later, that’s exactly what happened.

An unnecessary and unauthorized hold

In less than a month at Brooklawn, Ja’Ceon had already been placed in three physical holds, all involving the same staffer: youth care worker Jillian Parks. Parks is referred to as YCW #5 in the state's report.

Ja’Ceon’s therapist and the facility’s residential manager had a meeting on July 12 where they identified Parks as a trigger for him. There was no evidence that his treatment plan was changed to reflect this, but the residential manager and therapist told investigators they directed Parks to not get involved in any future holds with him.

Parks clocked in at 2 p.m. that afternoon.

The state’s report shows that at 2:24 p.m., Ja’Ceon, still isolated in his room, once again signaled for a staff member. Whitlow said when she approached his doorway soon after, she saw that Ja’Ceon had wet his pants again. During their interaction, she said Ja’Ceon picked up his plastic water bottle and threatened to throw it at her, but he didn’t act on it.

Within seconds, camera footage shows Parks walking over to his doorway and entering his bedroom, out of the camera’s view.

To respect the children’s privacy, none of the bedrooms at Brooklawn are equipped with cameras. The facility’s policy states that staff should move children to the common area, the timeout room or any other area where it can be recorded if they need to use a hold.

Parks refused to cooperate with the state’s investigation and was not interviewed. But according to Whitlow, when Parks entered Ja’Ceon’s room, she immediately pinned his hands against the wall.

Whitlow said Ja’Ceon threatened to hit Parks and called her a “stupid bitch.” She said Parks then initiated what is called a standing cradle hold, pinning his arms to his hips while he faced away from her. The two of them lost their balance and fell to the floor, which is when Parks transitioned to a kneeling cradle hold. Ja’Ceon was sitting with his legs straight out in front of him while Parks kneeled behind him, and held his wrists at his waist.

Whitlow said she assisted by holding Ja’Ceon’s feet, and used empathetic language to try and calm him. She said they were laughing together because Whitlow had accidentally sat in Ja’Ceon’s urine.

A minute later, Francis, the shift supervisor, entered the room. Francis said she took over the hold because she knew Parks was not supposed to be involved in physical management with Ja’Ceon. But Parks stayed in the room and took control of his legs.

Francis told state investigators that Ja’Ceon was fighting hard to get out of the hold, which is why she didn’t attempt to move him into camera view. She said there was no indication that Ja’Ceon was having respiratory distress during the hold.

But Whitlow told investigators that when Francis took over, she pushed Ja’Ceon so far forward that his nose almost touched the floor, with his legs still straight out in front of him. Then she instructed Whitlow to go check on the other residents.

On her way back to Ja’Ceon’s room four minutes later, at 2:35 p.m., Whitlow said she heard Francis say, “Go ahead, throw up, throw up.” When she looked through his doorway, she said Ja’Ceon had thrown up a lot of clear liquid and chunks of food. He was crying.

By 2:36 p.m., nearly 10 minutes after Parks first entered his room, Ja’Ceon was unconscious. Francis told investigators that she felt his body “become dead weight,” and said she released the hold. Francis tapped on his face and said that she thought he was still breathing.

Camera footage shows Whitlow running towards the kitchen to grab a cold wash cloth and ice water. He was still unresponsive, so Francis dumped the ice water over him. No response. Soon after that, Parks initiated CPR and Whitlow called 911.

When first responders arrived, they said Ja’Ceon didn’t have a pulse.

A system that failed to protect him

The 122-page investigation into Ja’Ceon Terry’s death makes at least one thing exceedingly clear: The system that was supposed to protect him failed.

The only time staff members should resort to physical restraint, according to state and facility policy, is when a child is harming themselves or another person. And even then, staff members are required to get permission from a clinical consultant who is certified in emergency safety intervention.

When staff members restrained Ja’Ceon last July, he wasn’t hurting himself or anyone else. The 7-year-old said he was going to throw a plastic water bottle at a staff member and used a bad word.

And even though the state said the facility has monthly training on safe crisis management, the report shows that staff members failed to perform the hold safely, putting pressure on his abdomen and diaphragm. They also continued to restrain Ja’Ceon even after he began to throw up and show signs of distress.

Before the hold that killed him, Ja’Ceon was also subjected to an unnecessary isolation and ridicule by a staff member. And the facility failed to ensure his treatment plan reflected that he was often triggered by the same staff member time and time again.

Investigators reviewed the physical hold and seclusion report that staff filed after the incident, but the state’s report doesn’t say who wrote it. It said that Ja’Ceon kept trying to leave his room around 2 p.m. that day, but the video footage disproved this claim. They also wrote that Ja’Ceon “threatened to assault” staff and that he charged at Parks in his bedroom, which is why she initiated the hold. But in interviews with Whitlow and Francis, neither mentioned that Ja’Ceon charged at anyone.

‘Immediate jeopardy’

The Cabinet for Health and Family Services Office of the Inspector General determined on Sept. 22 that Ja’Ceon was placed in immediate jeopardy that day and issued Brooklawn a Level 4 deficiency, which indicates the highest level of harm.

The cabinet immediately removed foster children from all of Brooklawn’s units, not just the cottage where Ja’Ceon lived.

Ja’Ceon’s death was ruled a homicide by the Jefferson County coroner in September. He died of positional asphyxia, which means he was put in a position that prevented him from breathing adequately. Francis and Parks were fired shortly after.

The state’s investigation continued until November and a month later they announced that they would be revoking Brooklawn’s license to operate their psychiatric units.

In May, foster placements resumed at Brooklawn’s other programs, including its residential care unit, independent living and therapeutic foster care.

“The cabinet has set forth requirements that must be met for these placements to remain in effect,” a spokesperson for the cabinet said in an email. “When it is necessary to place children in the care of the state, the cabinet makes its best efforts on behalf of these children.”

KyCIR found that after Ja’Ceon’s death, the cabinet investigated Brooklawn’s other units too. Records show that there were six incidents at its residential care unit that were not previously reported to the cabinet’s Inspector General. The incidents were shared with the Inspector General’s Office during another agency’s investigation, according to the deficiency report. Two involved broken bones; in another incident, a child was slapped, punched and kicked by a staff member who was later fired. The facility violated several regulations, the state determined, including failure to protect a child from abuse and inappropriately performing a physical hold.

Ja’Ceon’s foster family sued Brooklawn last year, and in May the company agreed to a private and confidential settlement. The resolution came just days after the judge ruled that a former employee could testify about the abuse and mistreatment she said she witnessed while working there.

The facility is also still facing an additional lawsuit filed by a mother in November who said her developmentally delayed son was physically and emotionally abused there from July 2021 to March 2022. The boy told his mom he was choked by a staff member who was only referred to in the lawsuit as “Miss Debbie.” The facility said in its response that it didn’t have enough information to confirm or deny the allegation, and didn’t address the staffer’s identity.

A residential manager at Brooklawn who wasn’t working the day Ja’Ceon died told investigators that what happened in the last hours of the child’s life “made his skin boil.” But the impact of Ja’Ceon’s death was felt by more than just staff.

There were eight other children in the cottage that day when Ja’Ceon died – children who knew him, played with him and became friends with him during their short time together.

One child told investigators that when they heard how Ja’Ceon died, they cried and thought about killing themself. A different child said they wished they were put in the hold instead of Ja’Ceon, so that he could keep living.

But at least now, another child said, Ja’Ceon was in heaven.

Support for this story was provided in part by the Jewish Heritage Fund.