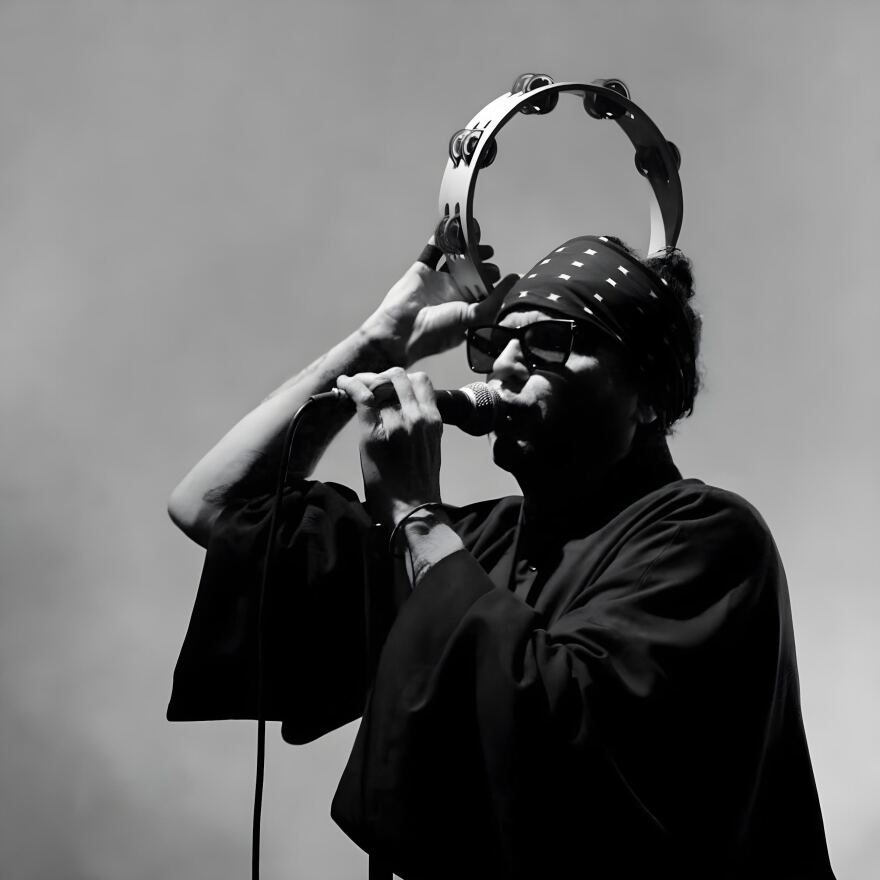

Ian Astbury isn’t looking backward. Not exactly. He’s looking through time like a prism—slicing past, present, and future into one jagged, glittering beam. “Nostalgia is an illusion,” he tells me. “Death Cult is PRP. It’s putting the original DNA back into us.” For Astbury, the resurrection of Death Cult—the short-lived post-Southern Death Cult band that bridged the way to The Cult proper—isn’t about playing the hits. It’s about rewiring the bloodline.

The new tour finds him pulling double duty, fronting both The Cult and Death Cult across the same stage. And while this isn’t the first time he’s revisited that early incarnation, it’s the most urgent. “We’re 28 days out. Shitload going on,” he says bluntly. “There’s a renaissance happening around us. All of a sudden, we’re everywhere.” He’s not wrong. Cult songs have crept back into cultural consciousness through Severance, Euphoria, even Happy Gilmore 2. “They’re picking up on a frequency that’s always been there,” he shrugs. “We’ve always been the outlier. The contradiction.”

But despite the renewed attention, the real draw is creative impulse. For Astbury, Death Cult is a return to “zero point”—a philosophical and spiritual reset. “If you have any kind of meditative process... you come back to the breath, to the zero point. That’s the moment you’re in.” It's no coincidence the tour is called Paradise Now. It's not a command—it’s a state of being. “If not now, then when?” he echoes, invoking a phrase once dropped by Ray Manzarek of The Doors.

Death Cult only lasted eight months back in 1983, but for Astbury, it marked a cultural inflection point. “1984 was the end of the 20th century,” he says. “Ridley Scott dropped that Apple commercial. The Cold War. We were recording next to the Berlin Wall.” He recounts having to navigate military checkpoints to play in West Berlin, opening for The Clash, getting rolled on the street, and crashing squats. “That kid was a coyote. I lived on the street,” he says of his younger self.

But that kid also shared a jazz cigarette with Paul Simonon and later opened for his band. “We were stealing their beer backstage. Classic Death Cult.” He tells it with a smirk, but the weight of the moment—survival, ascension, alienation—lingers beneath.

Even at their commercial peak, Astbury didn’t feel like he belonged. “Once MTV grabbed the band and we had Warner Brothers behind us... something didn’t feel right,” he confesses. “My friends weren’t at those velvet-rope parties. They were like Andrew Wood, coming up with Mother Love Bone.”

Astbury’s ambivalence toward fame is rooted in more than taste. “I was objectified,” he says. “Everyone assumed I was a dumb dumb, ‘hold my beer.’” British press called his mother a glue-sniffer and slung racial slurs his way. “She died of cancer on my 17th birthday,” he says. “And I wasn’t having it. So I spoke up. And they turned the volume down on me.”

That disconnect—between public image and personal truth—never resolved. He walked away more than once. “Everyone assumes you’re irrelevant if you’re not in the media. No. It was a personal choice. My dad was dying. I was coming of age. I started in this band at 19.”

Even as The Cult mutated through musical eras—goth, hard rock, Britpop-adjacent misadventures—Astbury chased his instincts. “Everything’s from the gut,” he says. “You don’t think about it until afterward. Then you go, ‘Why did I do that?’” And now? “We’ve already started,” he grins, when I ask what’s next for The Cult. “I’m obsessed with dark wave. Berlin. Brutalism. We’re not writing songs about sheep farming.”

He’s quick to defend his contemporaries too. When a joke comes up about Coldplay winning Best Rock Artist at the VMAs, he cuts in. “Coldplay never claimed to be something they’re not. They’re excellent at what they do. Transcendent. But I’m not talking about Coldplay. I’m talking about danger.”

Danger, it turns out, is the missing element. “Artists are terrified. Everyone’s frozen,” he says. “We used to throw guitars in the air and let them smash. Who does that now?” He gives props to Fontaine’s D.C., Idles, Patriarchy, Ethel Cain. “Patriarchy are raw. Ethel Cain kills me. Dust Bowl crushes me.”

Astbury wants more crossover. “Why not do one-offs with everyone you admire? Play with the Grateful Dead. Play with Lana Del Rey. Share toys.” He pictures a new kind of festival: spontaneous, collaborative, anti-corporate. “Gather the tribes,” he says again. “Where there is a will, there is a way.”

It all loops back to Death Cult. A brief, feral flash in time that now feels more urgent than ever. “The Death Cult shows? Savage. Somebody asked me to describe them. I said, ‘beatific savagery.’ It’s connected.”

Astbury is still running on intuition. Still catching frequencies. Still gathering the tribes.

And if not now… then when?

Watch the full interview above and then check out the video below.