Andrew Smith, 14, and his brother Christian, 11, wandered recently through grassy fields filled with trees, hacking away with pickaxes. Not in real life—virtually.In reality, the brothers were in the living room of their St. Matthews home, computers before them, playing their favorite game: “Minecraft.” In that Lego-like virtual arena, they can choose from countless worlds to “mine”—that’s what’s behind the hacking—explore, build things and even battle creatures.“You have freedom in the game. You can build. You can survive. You can do anything you want,” said Christian Smith, whose father is Ted Smith, Louisville Metro’s director of innovation.Soon, thanks to a group of coders, the Smith brothers could play “Minecraft” in a virtual version of Louisville created largely using public data.Louisville coders are trying to replicate the city in the popular game Minecraft.The “Minecraft” version of Louisville would be among the first real-life cities to show up in the popular computer game, which has sold more than 50 million copies worldwide and has become an online obsession for people like the Smith brothers.The project could boost interest in Louisville or be used as an educational tool—and it could also show the limitations of the public data available about the city.“So much of our social experience right now is sort of both physical world and digital world,” Ted Smith said.Louisville 'Minecraft' First Needs Good DataLouisville’s “Minecraft” replica will only be as good as the information that goes into it, said Michael Schnuerle, one of coders who is working for free on the Louisville "Minecraft" project.“The city collects very detailed geographic information about almost everything you see here,” he said recently, standing in front of the KFC Yum Center. “They have the exact width and shape of the road, the kind of surface that road is, the location of every street lamp, the location of every parking meter.”Schnuerle listed several other data sets like building layouts and heights, and underground sewer systems. But not all of it is open accessible data, or even easy to obtain if it is. He said every U.S. city collects different types of data, of different quality, in different levels of detail.“The state collects different information and then the federal government collects other information. So in some cases we have to piece together these disparate levels of information into one cohesive whole,” he said.Schnuerle’s group is trying to work with the Louisville/Jefferson County Information Consortium, known as LOJIC, which keeps the Geographic Information System data sets. The data could help make Louisville “Minecraft” as realistic as possible—think everything from sewer system data to the height of every building.But it’s not as easy as just giving away access to their database. Some data is continually updated, other data might need certain file conversions, and some is worth money to, say, the real estate industry. Plus it strains resources to pull or keep this data current, said LOJIC manager Curt Bynum.Schnuerle said the group may be two months from releasing the first edition of Louisville "Minecraft."The result of letting people play with open data may lead to more innovation or help solve community problems, he said. It might also showcase what other data could be useful.Currently on the "Minecraft" group's wish list are data sets of polling locations, voting precinct boundaries, all utilities, street lights, signs and signals. Without those, a Louisville "Minecraft" world can still be created, but what's presented would have its limits compared to the real world.The goal, Schnuerle said, is to create ways to visualize this data for others to see. Take the city’s crime numbers. The game allows users to play in “creative mode," with no creatures, or “survival” mode where creatures roam the night and you’re forced to fight them off.“So you could, theoretically, in areas of more crime have more of those creatures as a way to visualize the safeness of an area,” Schnuerle said.What Louisville Can Learn From DenmarkEarlier this year, Denmark became the first country to replicate itself using public data and "Minecraft."What followed was an experiment.The game normally allows gamers to use dynamite to collect resources. But TNT was banned by Denmark coders. Hackers still managed to sneak in dynamite and destroy parts of cities. American tanks rolled through Copenhagen.“It was just a part of the craziness in the first week after we launched it,” said Signe Egmose, who works in the Danish Geodata Agency that led the project. “Some built and some destroyed. It was funny to see how people reacted.”But Egmose said there are real physical benefits for the country.For example, she said "Minecraft" Denmark has been downloaded more than 300,000 times, and many of those are from outside the country.“We were quite surprised how crazy it was. I mean I’m talking to you right now and you’re in America. And people were just very interested,” she said.What was the Danish most interested in? What their homes look like, said Egmose.

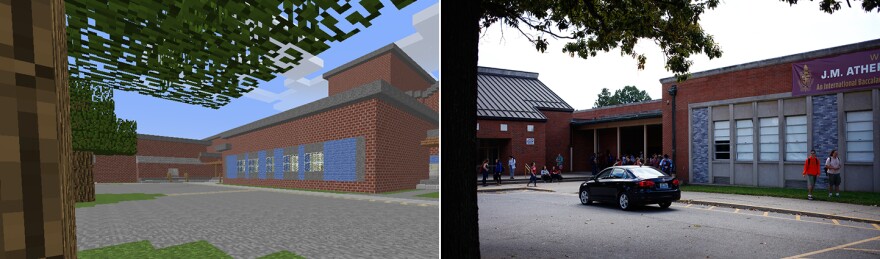

That may be true for the Louisville version, too.“I would probably go and try to find my own house,” said Andrew Smith.His brother Christian had another suggestion.“I would probably, first of all, try to find our school first and see if everything is block to block and see if I think it was the right block to use,” he said.This is also what coders like Schnuerle and city officials are hoping for—to engage kids with their community and learn about what they can do with public data at an early age.But more importantly, said Ted Smith, the game will give anyone a chance to build a new Louisville or create new things. In essence: think big.“It would be nice to have some of that energy unleashed on Louisville and our community. And having people dream big dreams about where they live,” said Smith.