Junkie XL talks about Zack Snyder’s Justice League the way mountaineers talk about avalanches — with awe, a little PTSD, and the sense that if you survive it, you’ve earned the right to brag about the view. “It was my Mount Everest,” he tells me, and he doesn’t mean that metaphor lightly. Four hours of film. Four hours of score. All of it rebuilt from the ground up because the first time around, back in 2016, was a miserable experience he wanted nothing to do with anymore. “I listened back to what I did and the negative feeling from that whole time period just came back,” he says. “I didn’t want that attached to something that finally felt great.” So the solution, naturally, was to wipe the slate clean and start over — the sort of thing musicians say they’d love to do with old work but never actually can. Holkenborg just happened to have a studio full of gear, Zack Snyder cheering him on, and eight months of pandemic isolation to give it a go.

Snyder wasn’t sentimental about the abandoned material either. “I’m not married to anything we did in 2016,” he told Holkenborg. This time, Snyder pushed him in the opposite direction: go bigger, get stranger, stretch the score as far as classical, rock, synths, and percussive mayhem could bend without snapping. “He really egged me on,” Holkenborg says. “To take it to the furthest levels.”

If that sounds like a lot, that’s because it is. But Holkenborg — who calls himself a “full-contact composer,” which is exactly the kind of phrase you’d expect from a guy who once scored Mad Max: Fury Road like he’d strapped himself to a flaming drum machine — leaned into all. The score blends orchestral grandeur with industrial grime and choral dread, all tied together with a through-line he says comes from playing nearly every instrument himself. “You can’t help it,” he shrugs. “If you play drums a certain way, you’ll play synthesizers a certain way, and you’ll bang on other materials the same way.” It’s a style by force of personality, the way you instantly know it’s Radiohead or U2 after three notes.

As for those choirs, “Human voices can be so scary,” he says, with a little too much delight. He cites 20th-century composers who practically weaponized choirs — Ligeti, Part — and found ways to inject that same “wheels-coming-off” instability into Steppenwolf’s theme. It’s church music for a villain who definitely would not be welcome in a church.

For all the score’s excess and violence, there’s structure: character themes woven through the film, many inherited from Holkenborg’s earlier work with Hans Zimmer. “Superman and Wonder Woman have themes that bleed over from Batman v Superman,” he says. Batman, however, needed a total overhaul. “His past is dealt with in the last movie. In this one, he moves forward. So musically, I could move forward too.” Cyborg, Aquaman, and the Mother Boxes all get their own identity, and the Justice League theme — teased in early singles like “Crew at Warpower” — becomes the big, muscular glue binding it all together.

Holkenborg says fans already imagine where cues belong in the film, sometimes with unnerving confidence. “Each DC fan has their own imagination about what this absolutely must be,” he says. Some think they hear Wonder Woman saving the day, others insist a certain timpani roll equals Batman punching someone extremely hard. “It’s interesting how music speaks to the imagination without intention.”

The monastic isolation of scoring during COVID didn’t hurt the intensity either. Normally he works with assistants buzzing around, lunch breaks, hallway conversations, the ambient noise of a creative hive. Instead he was alone, staring down an Everest-sized deadline with only delivery trucks and the occasional existential dread for company. “It was a curse and a blessing,” he admits. No distractions, but no lifelines.

You’d think one four-hour superhero epic would be enough for a while, but Holkenborg slid straight into Godzilla vs. Kong, which required a totally different musical brain. Director Adam Wingard wanted to honor classic monster-movie bombast while rubbing it up against John Carpenter-style synths. “He said, ‘I want old monster scores, but also a lot of 80s synthesizers,’” Holkenborg recalls. So the film gets everything from cavernous brass to pulsating analog electronics, plus surprisingly tender world-music textures for Kong. “There are so many emotional scenes for him,” he says. “It’s great to work with all those colors.”

Then there’s Army of the Dead, a sound-design heavy score leaning into emotional weight rather than zombie splatter. And no, he’s not giving away the twist. “I want everybody to have that ‘What?!’ moment I had when I first saw it.” Even after all these projects, he still wakes up, sits outside with a coffee, and marvels at his job. “I think, you’re a happy guy. You get to work with the smartest people in the room, with talented people, with crazy ideas. It’s so great.”

If climbing Everest sounds this joyful, maybe the point was never the summit — it was that Holkenborg found a way to enjoy the thin air.

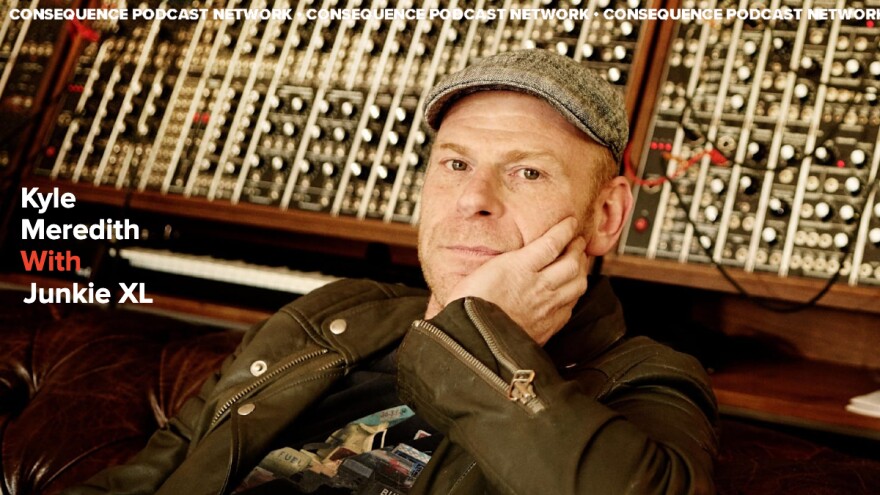

Watch the interview above and then check out the video below.